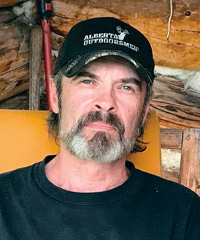

Outdoor Pursuits

with Rob Miskosky

From the Editor - January 2026

Alberta’s vast wilderness is home to some of Canada’s most iconic wildlife, including moose, woodland caribou and elk. These animals are not just symbols of Alberta’s landscape, they’re vital to our ecosystems and hunting traditions. But a tiny parasite, recently confirmed in the province, poses a grave new danger.

Known as meningeal worm (scientific name Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, or P. tenuis), this brain-invading roundworm is harmless to white-tailed deer but often deadly to moose, elk, caribou, bighorn sheep, mountain goats and antelope.

First detected in Alberta in 2024, its arrival in the northeast near Cold Lake has raised alarms among wildlife experts, hunters, and conservationists.

Imagine a parasite that lives quietly in one animal but wreaks havoc in others. That’s the meningeal worm. In its normal host, the white-tailed deer, the adult worms coil up in the protective layers (meninges) around the brain and spinal cord. They lay eggs that travel to the lungs, hatch into larvae, and end up in the deer’s droppings. These larvae are then picked up by snails or slugs crawling over the moist feces in the forest. When a deer accidentally eats an infected snail or slug while browsing, the larvae burrow through the stomach wall, travel along nerves to the spinal cord, and mature into adults—completing the cycle without causing much harm to the deer. But in moose, elk or caribou, things go seriously wrong. The larvae still migrate to the nervous system, but they wander erratically, causing severe inflammation, bleeding, and damage to the brain and spinal cord. Affected animals show symptoms that include weakness in the hind legs, stumbling, circling, head tilting, blindness, or even fearlessness as their brains fail. Most don’t recover and they become easy prey or succumb to paralysis and starvation.

For decades, meningeal worm was common in eastern Canada and the US, but Alberta appeared safe because of a drier climate and fewer suitable snails. That changed in June 2024. Wildlife monitors on the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range (these folks’ primary focus is monitoring caribou health, movements, population trends, and habitat use on the range) spotted a caribou acting strangely. Tests confirmed meningeal worm. Over the following months, five more cases emerged—four more caribou and one moose, all in the same northeast region around Cold Lake, extending northwest toward Fort McMurray.

The parasite likely hitched a ride westward with expanding white-tailed deer populations. This marks the first confirmed discovery in the province, though isolated cases have been discovered near the Saskatchewan border in the past.

Hunters are on the front lines and we need to be vigilant. If you spot a moose, elk or caribou acting oddly—limping, unafraid of humans, or circling—don’t approach or harvest it. Report it immediately to Alberta Fish and Wildlife through the Report a Poacher line (1-800-642-3800) or local offices. Provide location details and photos if you can. The province now tests all white-tailed deer heads submitted for chronic wasting disease (CWD) in the northeast for meningeal worm too. Hunters can help by continuing to submit heads for CWD testing.

Wildlife disease specialists have long monitored this parasite. Dr. Margo Pybus, Alberta’s Provincial Wildlife Disease Specialist, has researched ungulate parasites for years, including warnings about potential western spread of meningeal worm. Challenges include vast remote areas making full surveillance tough, there’s no vaccine for ungulate treatment, and controlling deer densities is not favoured by the public.

Once established in white-tailed deer, the worm is nearly impossible to eradicate. Snail habitats depend on moisture, so a drier southern Alberta grasslands may limit southward spread, protecting antelope, elk, and mule deer that reside there.

Experts are developing response plans, including public awareness and enhanced testing, but documenting population impacts takes time and the long-term consequences for Alberta’s wildlife is worrying. Alberta’s woodland caribou herds are already threatened so losing even a few to this parasite could devastate local groups. Moose numbers have declined in parts of the province too, so meningeal worm adds pressure, potentially adding to a drop in moose. Elk face risks too, though some may tolerate low infections better.

Historically, in eastern North America, meningeal worm contributed to caribou disappearing from large areas as white-tailed deer expanded. If it spreads widely in Alberta’s boreal forests, we could see similar declines here.

Yet there’s hope, as the worm may stay confined to wetter northern zones. Significant portions of Alberta, particularly the southern and southeastern regions, are considered having a semi-arid climate, characterized by light rainfall. Regardless, Alberta doesn’t need another threat to its wildlife, considering that CWD continues to wreak havoc with its constant movement west. A recent announcement allowing fenced hunting in Alberta also poses a threat to both the image of hunting and to the continued spread of CWD. Hunters, conservationists, and policymakers must prioritize wild populations, disease monitoring, and fair-chase ethics to safeguard Alberta’s wildlife populations.

For the previous Outdoor Pursuits article, click here.